Russian hackers exfiltrated data from from Capita over a week before outage

Capita have finally admitted a data breach, but still do not think they need to disclose key details of the incident to customers, regulators, impacted parties and investors. So in this piece we shall dig into the details using open source intelligence, and prove Capita was penetrated by Black Basta ransomware group using Qakbot phishing to deliver hands on keyboard access for weeks — and question if the playbooks organisations are using to handle ransomware groups are fit for purpose in 2023.

Almost two weeks ago, I wrote a piece called “Black Basta ransomware group extorts Capita with stolen customer data, Capita fumble response”. The piece documented how, from the start of the incident, Capita failed to disclose key details to stakeholders — and directly evidenced a Russian based double extortion (ransomware) group were serving stolen Capita customer data.

Off the back of that piece, Capita still failed to issue any update to markets or investors, failed to acknowledge ransomware, failed to acknowledge the link to Black Basta, ignored the problem for a week, and then tried to pretend to press that data leaked by the ransomware group may be “public domain”. Black Basta’s data was obviously not public domain data, and it is sadly very clear Capita have a serious situation they are failing to disclose properly, or attempting to wordsmith around.

Why does this matter? Capita handle £6.5billion of UK government contracts. They have multiple business units running national security level importance functions — for example, they are involved in the SC and DV security clearance process as part of the National Security Vetting, directly collecting personal information for high risk UK government roles — under the banner Security Watchdog — a business which Capita own and is directly impacted by this incident.

Capita are currently selling Security Watchdog to another company:

As late as Tuesday they told investors there was no evidence of data leak (from a member of LSE’s forum):

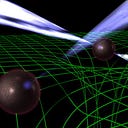

They then last minute rescheduled an investor day to the following month (links in the images, by the way).

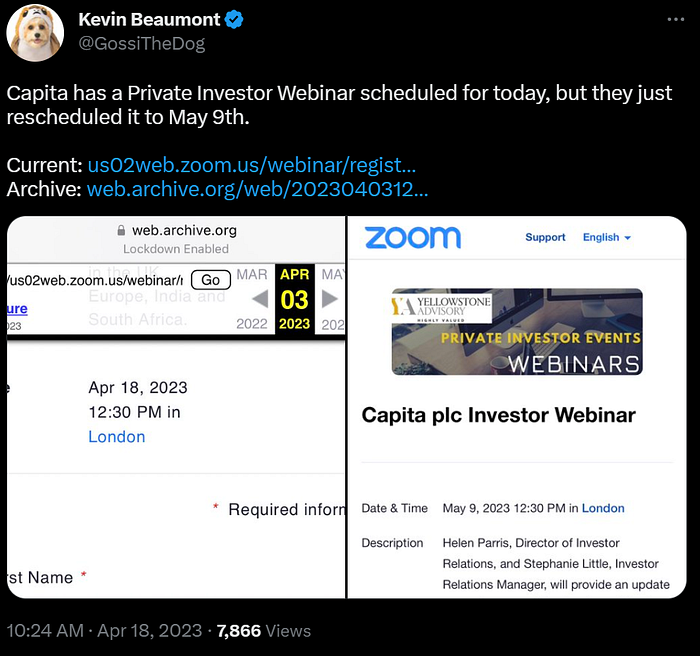

As late as yesterday they told the BBC there was no evidence of data leak:

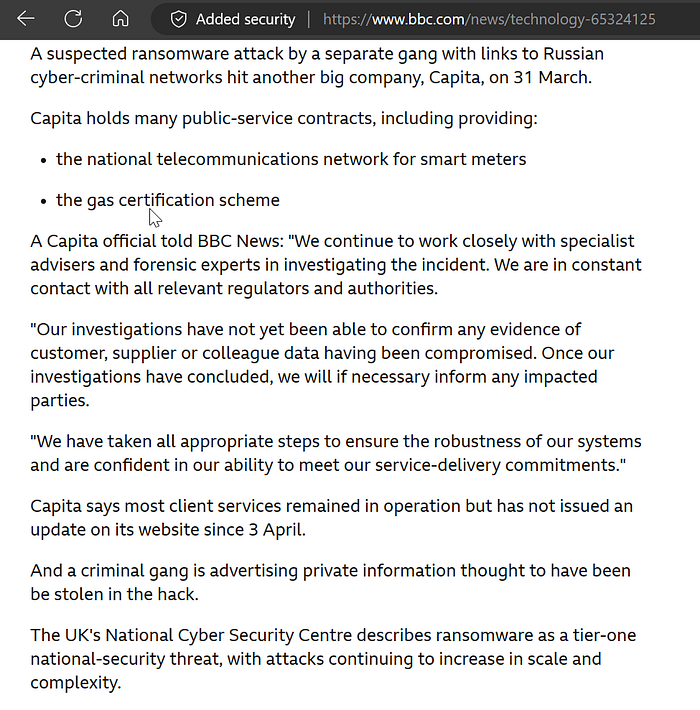

After the BBC piece, I tweeted that I was preparing to publish this blog post:

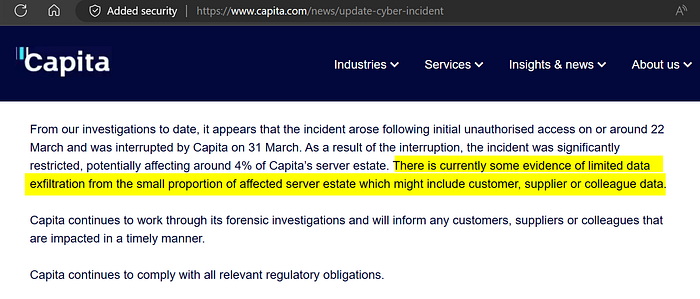

At market open this morning, Capita suddenly disclosed a data breach impacting the exact wording around data they had been claiming was not breached hours earlier:

This is also the first admission the threat actor gained access on 22nd March. Previously, they said 31st March — the date of the “IT Incident”.

What happened at Capita?

As we know from my previous post, Black Basta have Capita data screenshots on their ransomware portal. This was found by these technical steps:

- Open Tor Browser

- Look up ransomware groups

- Find Capita

As of today, it is still there, although hidden from the index. Typically, Black Basta exfiltrate around 500gb of data per victim — split across more than 200 victim organisations over the past year.

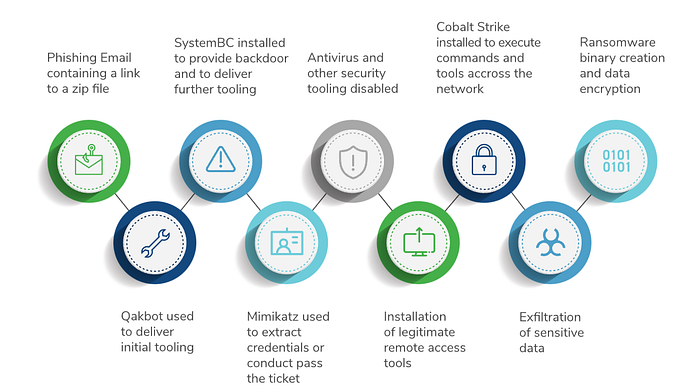

Black Basta typically gain access via Qakbot, a long standing email phishing toolkit that allows ransomware actors to gain initial access into end user PCs. Here’s a writeup from Kroll on a typical Black Basta incident:

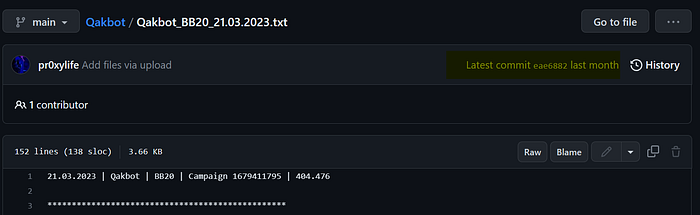

Qakbot has been around for many years, and is under heavy surveillance by both commercial CTI providers and independent security researchers. When looking for Capita, it was pretty easy to find them:

Capita became infected from a Qakbot campaign on March 21st — showing infected endpoints checking into Qakbot BB20.

Volunteer groups such as Cryptolaemus monitor Qakbot, and form much of the detection used by commercial providers such as Microsoft. Cryptolaemus don’t get the credit they deserve for being the dam to threats like Emotet and Qakbot.

Back on March 21st, pr0xylife on Twitter publicly documented Qakbot using BB20 — technical indicators follow:

Qakbot BB20 is Black Basta. Their operators use it. According to Capita in their press release, their initial unauthorised access began on or around 22nd March.

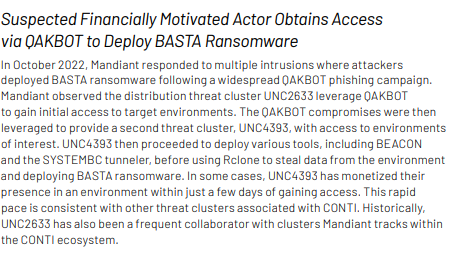

Mandiant’s recent writeup is relevant for Qakbot:

From there, the threat actor continued accessing Capita’s network and took data from Capita’s systems and business units. Even after the outage, through to April 19th, Capita claims there was “no evidence” data was taken. You might want to raise your eyebrows at this point.

Exfiltration of data by Black Basta is also heavily monitored by security researchers, including what data is moved where and when:

Capita do not seem to have understood the importance of this still.

On March 31st, the threat actor attempted to initiate a destructive attack which was quickly foiled by Capita’s intervention.

Unfortunately from that point onwards, Capita have failed to properly disclose what was happening.

How can organisations protect themselves from similar attacks?

Kaspersky said yesterday they are seeing a “significant increase” in Qakbot activity. They are correct. Black Basta, which appears to include former members of Conti ransomware group given shared infrastructure, are one of a number of groups using Qakbot as initial access to organisations — they then steal data, and try to hold companies to ransom. These groups are causing disruption to civil society, holding to ransom schools, colleges, hospitals and businesses.

It is a serious threat to all organisations which should be met with both a response by government, and businesses.

From a high level, I would recommend consulting the NCSC’s page on mitigation malware and ransomware attacks, and related documentation:

From a technical level with Qakbot, essentially:

- Make sure you have antivirus and Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) software. Microsoft Defender for Endpoint is good.

- If you use Microsoft Defender, turn on tamper protection. Ransomware operators usually terminate security controls. Stop them.

- Make sure you read the alerts and resourced to action them. This is the #1 cause of ransomware misses I saw at Microsoft: nobody read the alerts, or they didn’t understand what to do. Basically every case had alerts like a Christmas tree — the burglar alarm was going off, but everybody put ear plugs in as they couldn’t resource responding.

- If you see alerts for Qakbot, isolate the PC and lock the user account until you’re sure things are safe. Go in hard.

- If you see alerts for Cobalt Strike, isolate the PC. Go in hard.

- If you see alerts for SystemBC, isolate the PC. Go in hard.

- If you have the ability to afford Microsoft Defender for Identity, consider it — it’s good, and will alert for common ransomware group activity out of the box. You need to be able to read and process the alerts, though.

- If you have AV and EDR tooling, you should look at the options available for response and pivot towards more automated response. For example, in Defender enable automatic remediation.

The average dwell time — between alert to incident — with ransomware is 9 days, according to Mandiant’s recent M-Trends report. You have a window to intervene.

If you can’t resource this internally, outsource detection and response to a good provider. While there are terrible Managed Security Service Providers, there are also great MSSPs who provably do this well for small to medium sized businesses.

If you’re a school or least cost company, lobby government for better action on ransomware, and take less risky technology choices — for example, many schools find Chromebooks and Windows 11 S Mode is more appropriate for their risk appetite as ransomware simply isn’t able to run.

For recent Qakbot runs, I published custom detections for MDE for runs from OneNote:

I also published rules for finding all internet exfiltration using rclone:

Additionally, although completely undocumented online, after talking to other victim orgs, Black Basta also use Zinstall (and FileZilla) for exfiltration:

Lessons learnt

Before I continue, I just want to point out serious security breaches suck, and we shouldn’t blame the victim as a rule. I’ve been on so many of big incidents over the decades I’ve lost count. It is also very easy to quarterback incident response poorly. From a technical containment point of view, based on public statements, it appears this went very well — within days of the outage they had the situation under control. Nobody sane would challenge that, and Capita should be applauded for the initial containment.

What we should, as an industry, push for — I think — is a balance of transparency. This is clearly a major incident involving legal, contractual and ethical disclosure requirements.

From the beginning, the statements to public and customers about the incident were simply misleading — from calling it an IT outage to pointing the finger at Microsoft 365, the incident has started on the wrong foot and is now the textbook example of taking a security breach and amplifying it, while trying to minimise it. Being self interested in a modern world doesn’t work. Placing customers last will backfire.

It’s 2023 — it’s okay to admit to a security breach — and it’s nowadays much less okay to try to cover one up. Ransomware attacks happen — recent history shows many examples of orgs who over communicate at the beginning fare better and actually end up reducing media coverage. There are so many ransomware stories that most media outlets don’t cover them any more. They will investigate “IT incidents” and unclear “cyber incidents”… as they might be something interesting, i.e. not ransomware.

Capita stepped on a landmine which they didn’t need to. We can all learn from that. Capita are learning the hard way that cybersecurity has changed.

Back when the incident began, the Capita CEO declared Capita’s response to the hack “will go down as a case history for how to deal with a sophisticated cyberattack”. In reality, Capita risks getting caught up in this incident for years over transparency concerns.

Yesterday, at CyberUK, Oliver Dowden stood on stage and declared ransomware a national security issue. The UK government now classes it as a tier 1 threat, the same as terrorism. The way we protect society from these threat actors — Russian ransomware groups — needs considerable change, as clearly the response over the past 10 years hasn’t worked well.

This incident needs to be the textbook example that changes the response of companies. Ransomware sucks. We can all defend better if we talk about it. We all suffer when we don’t.

You can follow me on Mastodon for cybersecurity updates.